Theology and vocation - a survey: Part II

The last talk I gave to theological educators as a Kern Family Foundation fellow

So while a cruciform understanding of vocation shows us ways that vocation is not about choice and fulfilment but rather about a way of living and giving that has an ascetic dimension, yet we are to walk it because of the joy that is set before us.

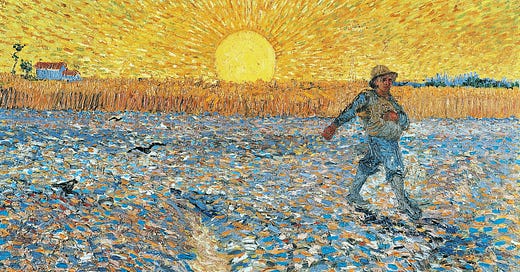

To put this in more earthy, gritty terms, as Luther did, when we work, however constrained our choice of that work, however humble or unpleasant our doing of it, we are answering God’s call. Whether or not we chose our work, even whether or not we feel love toward those we serve, yet God does, and it is God (Luther says) who places us vocationally in these relationships of service—indeed who serves others through us. Vocation is not most fundamentally about our choice, our motivations, or our feelings. We will all in our lives experience vocations that we never asked for—caring for an aging parent, or a disabled child, or a work colleague going through a hard time. These are surely vocations, but not ones we choose.

We see the same dynamic in our paying work. Why do we get paid for what we do? Because we are providing a service that other people value. The money is a measure of the value of the service we provide to others through our work, whether or not we have a passion, a fit, a fulfilment, or even much choice in the doing of that work. Think of our experience of continuing to serve students through a pandemic when we could not even be face-to-face with them. Whatever our choice or lack thereof, our work becomes a God-given providence to those we serve.

That is the Christian story of vocation. And that is why vocation is not just for the one percent. It is not a special privilege for the elite. It is a calling for all people, who do all kinds of work, not out of a quest for self-fulfillment, but because of the Christlike, the cruciform, and (don’t grow weary or lose heart!) the joy-giving call to serve our neighbor.

Having said this, instead of going on to offer any hard-and-fast definitions or rules for vocation, I want to point instead to one current conversation in the pages of the summer issue of Christian Scholar’s Review – which most of you know is a journal that has served Christian faculty members for many decades. I highly commend this issue to you – its theme, from cover to cover, is vocation.

So, just a taste:

Paul Wadell starts his article on learning to love through our vocations with this observation: “Over the last twenty years, a remarkable renaissance has taken place in thinking and writing about vocation: its richness, promise, substance. . . . Clearly, something significant is happening—something exciting, energizing, hopeful, and undeniably timely.” He then adds: “Maybe the timeliness of this renaissance is due to a realization that living vocationally rouses us to transcend ourselves in love and service to others—and that, in doing so, we can help to build a better world. Or perhaps, as the last few years have dramatically shown us, something needs to change—socially, economically, and politically—if we are to live into a future that is worth having for anyone.” [103]

Nazarene scholar Joshua Sweeden, in a review essay that includes a new book by elder statesman of vocation scholarship Gordon T Smith, writes, “Smith seems disinterested in interpreting calling through the lens of self-fulfillment or self-actualization. Instead, the particularity of calling . . . is about ‘doing what is needful’ and stewarding one’s capacities, gifts, and relationships within a sphere of responsibility. Smith refers to this as ‘vocational integrity:’ the ‘gracious acceptance of who we are,’ the ability . . . ‘to [do] the work required in this time and place.’” This could certainly be the prompt for a rich conversation! Smith’s book, by the way, is titled Your Calling Here and Now.

Sweeden’s essay also covers Susan Maros’s book Calling in Context and Brent Waters’s volume Common Callings and Ordinary Virtues. He concludes with a reflection on the overlooked importance of place in a Christian understanding of vocation today. He says, “People desire meaningful lives and professions but were often paradoxically taught to ignore or overlook those places and communities to which they belonged.” He then quotes Walter Brueggemann on modern placelessness, the empty promise that we can all lead “detached, unrooted lives of endless choice and no commitment.” The result of that rootlessness, as Brueggemann said, has been meaninglessness, since “there are no meanings apart from roots.”

All of this builds on Martin Luther’s core teaching that we have vocation anywhere we are in relationship with persons whom God has called us to serve in some way. From the mundane, intensely place-oriented and everyday material of our vocations, God provides for the flourishing of many.

Gesturing to such diverse thinkers about vocation as Luther, Calvin, Baxter, and Wesley, Sweeden concludes, “self-fulfillment or discovery of purpose are not part of their guiding theological questions.” Rather, stewardship is the appropriate biblical language that emerges, “shift[ing] calling and vocation from primarily an exercise in self-actualization to an opportunity for authentic participation in God’s commonwealth.” Yes, we must be careful, because the genuine submission, self-denial, and duty required within a Christian understanding of vocation can open a potential for abuse. Yet our vocations can also be a source of great joy. I think this is true precisely because of the access vocation gives us to a “participation in God’s commonwealth,” in Sweeden’s felicitous phrasing.

Again, I do commend this issue of Christian Scholar’s Review to all of you. Other highlights include an essay by Christian psychologist and scholar of vocation Bryan Dik, on how psychological science can help us understand work as calling; a pedagogical case study of how a class assignment based on an excerpt from Charles Taylor’s Ethics of Authenticity helps students push back against unscriptural individualism in their vocational understandings; and an excellent series of book reviews that amount to a map of the current state of vocation scholarship.

(Continued in following posts)