Theology and vocation - a survey: Part I

The last talk I gave to theological educators as a Kern Family Foundation fellow

The following is an after-breakfast talk I gave in August of 2023 to a group of theological educators gathered for an intensive workshop-based conference in Milwaukee, WI - hosted by my team at the Kern Family Foundation.

As it turned out, this conference was the last significant piece of work I did for Kern before they decided to withdraw from their fifteen-year effort to deepen and extend the faith and work movement within American theological education—and I started looking for another job! (I should add that the Kern Family Foundation still supports the faith and work conversation within the church, through the pastors’ network Made To Flourish.)

The talk laid out a brief survey of scholarship on vocation and work across a number of theological disciplines, unpacked several key ideas related to the biblical concept of vocation, then suggested a path forward for theological educators seeking to help their students explore these themes.

This morning’s brief plenary session will take the introductory video you’ve watched as a jumping-off point. I’d like to build on that video in three ways. First, since I brought the faith and work movement up in the video but didn’t say much about it, I’ll offer a few brief comments on where that movement has been and where it is now. Second, I’ll go a little deeper with you on a biblical understanding of vocation. And third, I’ll suggest some scholarly avenues that still need exploring on the interrelated areas of vocation and the church for the life of the world.

First then, a couple of comments on the faith and work movement—or at least, the phase of that movement that began in the 1980s, according to Princeton scholar David Miller.

I realize that some are skeptical of this movement–and not entirely without reason. For its first decades, it was both narrower and shallower than its name promised. Narrower, because it was really just about faith and business. Shallower, because the faith part of it tended to get written and led by laypeople who had given up on the church ever addressing their needs in a helpful way.

In this century, though, the movement has both broadened and deepened. Pastors are slowly integrating practices around vocational spirituality in their churches and—importantly for us as theological educators—a rising number of scholars are publishing nuanced, careful research at the intersection of faith and work.

We’ve seen scholarship in the past couple of decades from many streams of the evangelical movement that has explored a wide variety of issues surrounding what we may broadly call “faith and work.” I’m going to leave out a lot of excellent scholars, but here are a few representative names. I think of biblical scholarship from NT Wright, Darrell Bock, Jonathan Pennington, and John Taylor. Theological scholarship from Miroslav Volf, Darrell Cosden, Brent Waters, Scott Rae, and Greg Forster. And in a sub-field of Protestant thinking we might call “practical theology,” on the doctrine and experience of vocation, we’ve seen excellent work from Gordon T. Smith, Gene Edward Veith, Mark Schwehn, Jason Mahn, and others.

And again, we have theologically minded pastors and practitioners such as Tom Nelson, John Mark Comer, Amy Sherman, Katherine Alsdorf, and the late Tim Keller who have addressed this field with both biblical fidelity and alertness to our current American cultural moment.

Alongside such evangelical sources we have the rich tapestry of Catholic Social Thought which continues to be extended today, as well as the work of contemporary American Neocalvinist thinkers – among them Nick Wolterstorff, Craig Bartholomew, Vince Bacote, and Rich Mouw and his students such as Matt Kaemingk, Jessica Joustra, and Cory Willson. Particularly notable in recent faith & work literature is the excellent book by Kaemingk and Willson, Work & Worship.

In short, we’re living in a time of renewed and increased attention to faith-and-work questions – not just popular but also scholarly. The movement is growing, evolving, and most important, deepening.

. . .

Now, a bit more on vocation. Obviously a full and nuanced understanding of this important concept would take much longer than we have. Also, as with so many important theological ideas, there is no one universally accepted understanding of vocation. Many interpretations and layers of complexity lie in wait for those who explore it. For the topic invites not only questions about the discernment of what kind of work we’re supposed to do, but also about matters such as these:

· how vocation is or is not related to our desires or even our giftedness,

· how important subjective dimensions are vis-à-vis objective duties of service to others,

· how personal vocations mesh or don’t mesh with the missions of our organizations and institutions, and perhaps most importantly:

· how what Reformation thinkers called our “primary” calling as Christians under the Lordship of Christ should relate to our many “secondary” callings in the particularities of our households, neighborhoods, cities, and workplaces.

· And of course, that’s just scratching the surface!

Maybe the most important thing I’ve learned about vocation relates to a question we often hear; in fact, one we may have asked ourselves: “Isn’t the whole vocation conversation an inherently elitist discourse, that only the ‘one percent’ get to indulge in?”

Behind the question, it seems to me, is the assumption that since while most people in the world must work simply to survive, only well-resourced Westerners seem to have the privilege of choosing their own path in their working lives, therefore only they get to think of their work in terms of vocation.

Here’s the problem with this line of thought: it assumes vocation is all about choice and self-actualization. And indeed that is what our culture has taught us, and what we have taught our children, even in the churches. We might call this the Disney narrative of vocation: Follow your heart, find your passion, and you’ll get to live out your own perfectly fitting, fulfilling career path.

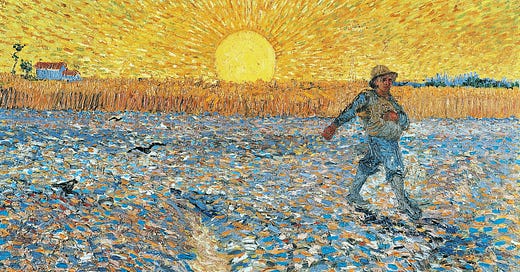

But that’s not the way the Bible talks about the call to work. Rather, it speaks of work as a given, a mandate; in fact, not just given but imposed by God. From the very beginning, God gave humans the job of cultivating and stewarding the good things he has made, thereby serving both God and neighbor.

In fact, in opposition to the “privileged choice” understanding of vocation, for Christian thinkers as diverse as Gregory the Great, Martin Luther, and John Wesley, our vocations actually often manifest as a cross to bear rather than a path to self-fulfillment – at least as the world counts self-fulfillment.

You may be thinking – what the heck is Chris talking about? Didn’t he say in the video that we may expect joy in our vocations? How does that fit with an understanding of vocation as cruciform?

I don’t pretend to have a final answer for this question. But I think of the first few verses of Hebrews 12. This passage speaks of casting off the sin that entangles us and running the race marked out for us with perseverance. And it tells us we are to do this because when we fix our eyes on Jesus, we see that he endured the cross “for the joy set before him.” Keep your eyes on Jesus, the author of Hebrews says, and “you will not grow weary and lose heart.” Because there is also a joy set before us no matter how hard the path.

(Continued in following posts)